A Conversation with Ash Brandin: How the Psychology of Video Games Should Change the Way We Teach our Kids

General

![]() Posted by: Kosciusko Connect

2 years ago

Posted by: Kosciusko Connect

2 years ago

The overall reputation of video games among parents and educators is darkened by our understanding of screen time and violence. As an educator, Ash Brandin has investigated in-depth the immersive quality of gaming, and how it intrinsically motivates users to keep strategizing and playing without any physical reward. Brandin seeks to incorporate these tactics into the way students learn and how teachers design classroom environments and curricula.

Let’s dive into our conversation with “The Gamer Educator,” and challenge our perspectives with a new look at into the digital world.

What do you most want educators to understand about the relationship between kids, learning, and video games?

AB: My message for educators is, when we don’t see kids’ interest in things like video games as valid, then the message we’re sending them is: “That’s not something we do at school, therefore it’s not an academic thing, and therefore, that’s an interest you should keep to yourself or that doesn’t somehow relate to what we’re learning at school.”

When we see validity in a student’s interest in things like video games, suddenly we’re able to relate to it, pull from it, and refer to it in ways that can expand student learning and allow them to connect more with what they’re learning in school and also realize that those things apply to what they might care much more about in their real life. It’s the same way that we try to connect with a kid who likes to play volleyball: we might not play volleyball, but we’ll still ask them about it because we view it as a hobby that’s worthy of validation and acknowledgment.

When we do the same thing for gaming interests, even if we don’t share them, then we’re sending that message of, “I care about you and your interests, and maybe there are things here than can somehow weave into or support what we’re learning in school.”

Teachers and parents often have strong stereotypes of video games and their potential negative influence on children. Is this the same stereotype that’s moved from TV to Netflix to social media, or is it rooted in something unique from other forms of media?

AB: There’s always something we’re going to blame and attribute to youth and their disenfranchisement. There’s always a thing, whether it’s video games, arcade games, TV, or CDs. I found an editorial from 1929 about the dangers of the radio. It said that people aren’t going to think for themselves – they’re going to let the radio think for them. It’s the same message. It doesn’t really change; it’s just the method. Now we look back and say that’s so silly, but we say the same thing about other technology now.

What’s been true for all those things as technology evolves is that the technology is not going to go away. It’s going to change shape, it’s going to change ubiquity, and it’s going to change appeal. But we’re not going to end up in some technologically absent world.

There’s resistance to acknowledging that playing video games is a way kids, and many adults, spend their time. What’s the end goal of the stereotype? We’re not going to get to a point where the world doesn’t have mobile games and other things that kids like. The longer we hold out on that, the more it creates a gap between kids and their interests, and adults and their lives. That’s a gap we must figure out how to bridge. It doesn’t mean we have to think that video games are the best thing kids do with their time, but we need to acknowledge that it is a way kids use their time and it’s a part of their lives.

Stereotyping video games is a multifaceted problem. One issue comes from some research that was very popular in the early 2000s that has largely been debunked, but still gets cited quite a lot. It tried to show some negative relationships between video games and behavior. It was so prevalent when it came out that it laid an academic foundation for what many think video games do. That affected a lot of people and their perceptions, especially people who work in education who maybe learned this when they were in college, and that’s still their assumption.

Another factor is that we don’t tend to put a lot of value on leisure that is just for its own sake. Other leisure activities we tend to value because they’re still somehow productive – someone is bettering themselves, learning or creating something, or serving society in some way. Video games largely appear to be truly leisure. Although kids might be gaining some skills from it, we’re not necessarily seeing those skills, and we often don’t see the effort and thought process that goes into it because it’s invisible to us. It seems like it’s pure leisure, and I don’t think we always value that as a good use of time.

Video games act as a very good scapegoat – they’re easy to blame because they’re not a person or an agency. It’s a lot harder for us to take personal responsibility for things we might have a hand in, both societally and individually. An easier excuse is, “It must be the video games!”

What role do the immersive quality and role-play aspects of video games play in parent and educator perspectives?

AB: Parents worry about things like violence. I remember growing up in the late‘80s and 90s when everyone was worried about Power Rangers and how kids would enact things they see on TV. We hear the same thing now for video games because they feel so much more real than TV. But kids aren’t dumb – they know what’s real and what’s not. Even if I keep my kids from video games as long as I want, one day they’re going to be exposed to it in some way because they go to a friend’s house, or stumble upon it somewhere else, or they move into a college dorm and their roommate games. Eventually, they’re going to encounter it.

When we accept that this is something we need to help them navigate, then we can have important conversations. If we’re concerned that they can’t differentiate between something fake and something real, abstaining is not going to give them an education. Instead, we need to take the time to ask them, “Why is it okay to do this? Would you do that in real life?” If we have those conversations about the skills we’re concerned about, we’ll often be surprised that our kids can make that differentiation. And if they can’t, then we know that’s a place we need to step in and help change the way they’re interacting with the content.

Sometimes people assume that I talk about accepting video games as part of kids’ lives and therefore, I must mean it’s a blanket acceptance of all of them, but that’s definitely not true. Just like every other part of media and every aspect of our kids’ lives, we decide what’s okay and what’s not. That doesn’t stop being true for video games just because we might not understand them. We might say, “I’m not okay with this game,” for whatever reason. We still get to impose boundaries around it.

When we find ways to have boundaries and limits, and have those conversations around why this is okay in some cases and not others, we are building up those skills of being able to differentiate content and being able to expose our kids to things we feel might be okay for them.

How did you start researching these topics, and when did you realize you wanted to implement what you learned in your own classroom?

AB: What’s funny is I decided to do it first, and then I looked at research to see who else was doing it. I really didn’t find very much. I first started looking at the research when I was finishing my master’s degree. At the time, I was in music education, and it was the height of Guitar Hero and Rock Band being popular. The way those games teach kids to play by pressing the button at the right time and color coding is pretty similar to how we teach beginning string players in orchestra. I saw that and thought there were probably a lot of string teachers who were taking advantage of the similarity and using the games. I thought, “Isn’t it so cool that this thing we really want to teach kids is something they already want to go home and do that teaches a similar skill?”

I turned to look at research at that point and couldn’t find any evidence of teachers using it. The very little I could find was about games truly designed for education, or information written for teachers as if video games were alien technology from another planet. I remember reading this article in a music teacher’s magazine around 2008 that was like, “What is a Nintendo Wii?” and the Wii came out in 2003. Teachers seemed so far removed from awareness of technology, let alone how they might use it in a classroom.

I remember that being an “aha” moment for me and realizing, either this really is where our teachers are at, or education as a whole thinks they are. It doesn’t really matter because if big education journals think that’s how removed teachers are, then this is how they’re going to address it, and it’s going to be self-fulfilling.

How did that research and piqued interest benefit your educational perspective and how you approached your teaching methods?

AB: I thought about the psychology – how is it that games get us to do hard things, and how do we imbed that in education? It’s a hard sell to say to teachers, “You need to haul an Xbox into your classroom and get all this technology working, and somehow that’s going to impact students in a positive way. Rethinking the curriculum we use and structuring it in a way that feels more game-like is an easier sell, and certainly more practical.

That’s where I started – rethinking the structure and presentation of content I already had in a way that felt more like the games I knew my students were playing.

Have you ever seen a teacher use this approach without associating it with a game’s structure?

AB: Many teachers try to make their lessons and classroom environments immersive and intrinsically motivating. It’s something video games do well because whatever they’re trying to target, they have to get you to learn controls and timing. They do that through immersion and motivation, giving the user a sense of buy-in and control over structure and exploration. All those things create that feeling of immersion, and you can definitely see kids learn a ton in their gaming environments because they feel that sense of immersion.

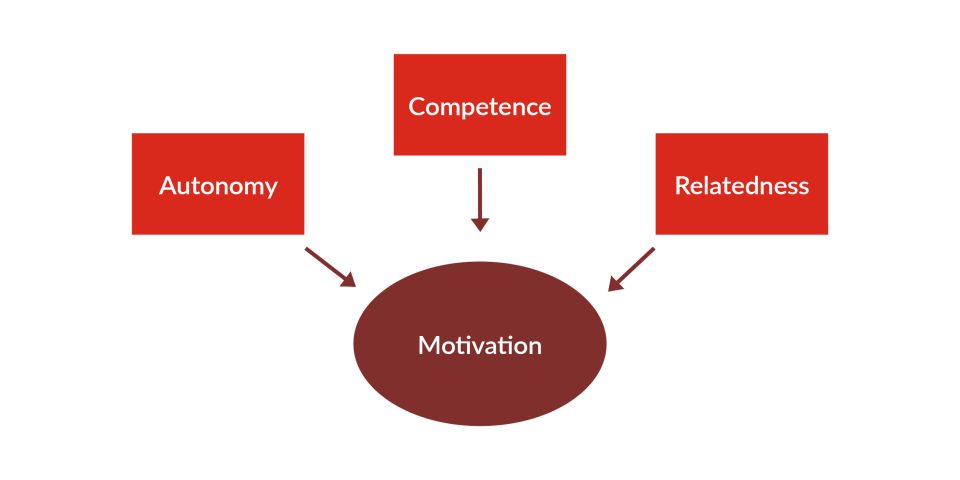

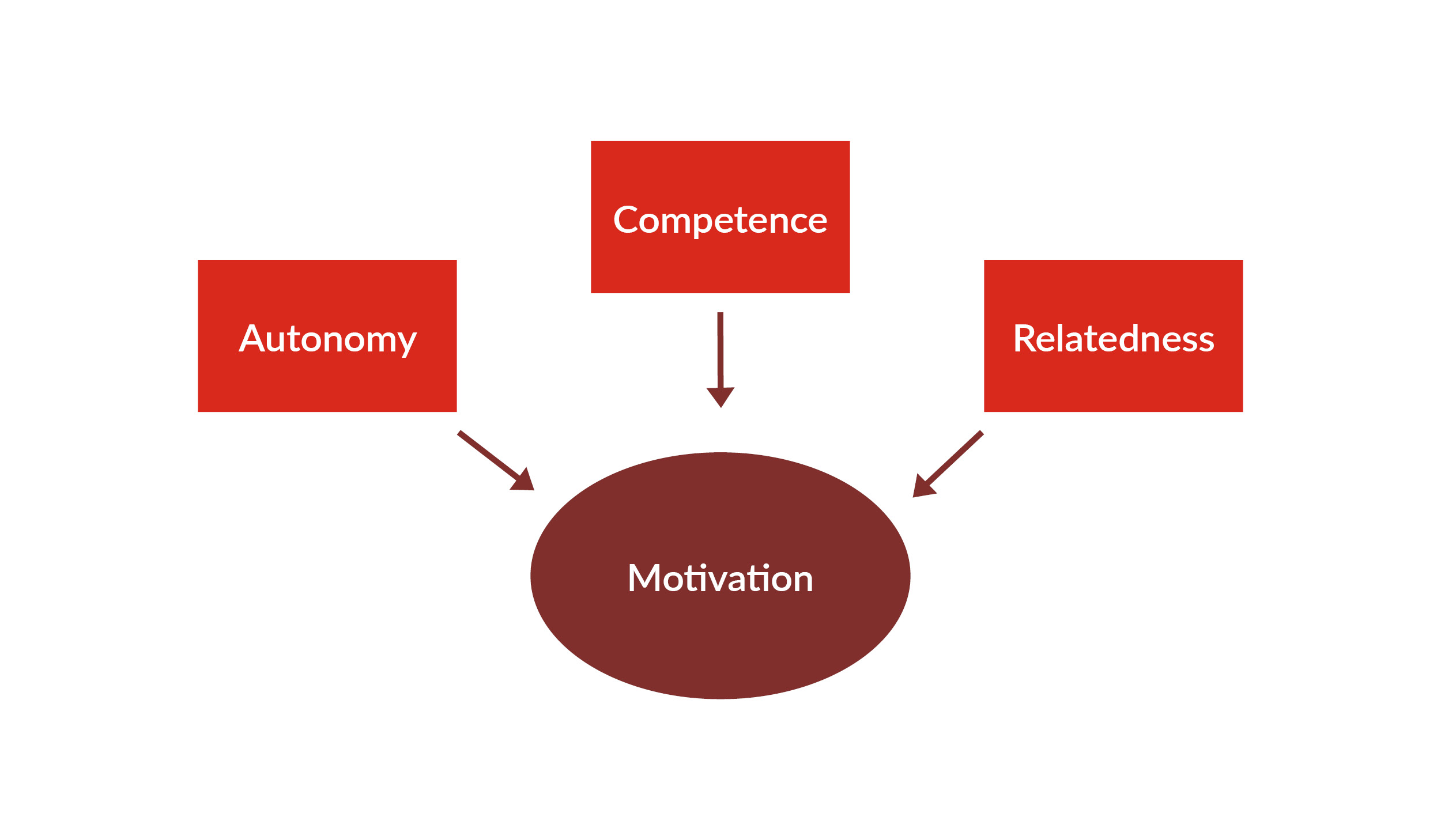

A lot of classrooms that try to be student-centered, hands-on, and exploratory tend to align that way. Video games are great at motivating us intrinsically, and they’re often doing that because they’re making us feel competent, autonomous – like we have control over what we’re doing – and related to other people. That happens often in video games because you’re the one deciding how many times you’re going to try to beat a level and what strategies you’re going to use.

We see this in certain pedagogies. The Montessori Method is a similar idea with children self-selecting things that they’re interested in to cultivate that feeling of motivation. This happens with project-based learning, or maybe you have an overall topic in mind, but students can self-select what they’re learning about or how they’re learning, with the goal being to get them more intrinsically motivated and interested in doing it.

Video games are often appealing to users because of the engaging stories they tell. How can parents and educators incorporate storytelling into their child’s education to develop intrinsic motivation?

AB: In education, if you’re learning about a time period or a specific event, maybe students are given the task or choice or learning about it from a character’s role. They learn about something from a perspective of a particular person or group in that event. Then they’re investing more in the character, so to speak, but also getting a perspective of that event. That can go in a lot of directions. Maybe you’re learning about the Civil War, and you have some students who are learning about it from the perspective of one side versus the other, or maybe from the perspective of people who are at home versus people who are enlisted.

Once they have learned more about their particular perspective, then you can shift and have them essentially teach other their different perspectives as a way of learning about the same topic from a different lens. They’re practicing mastery of something by learning it in a very focused way, but then expanding by teaching it to someone else and learning someone else’s perspective as well.

In home environments, it depends on what you’re trying to do. I find that sometimes asking open-ended questions gives you an idea of what your kid is interested in and shows them that you care about their interests. If you have a kid who’s really into creative Minecraft, maybe it’s asking them, “What are you making right now and how did you think to make that? Who’s going to live there?” – the same kinds of questions you might ask if you saw them drawing something or building with Legos.

Questions like “How did you get the idea for that?” and “What are you going to build next?” apply in the same way, and it’s the same thought process; it’s just showing up differently.

I think it can be really enlightening for the parent. We might not actually see a lot of what they do in the digital world, and we probably don’t see the thinking that’s going on. There’s often physical evidence of their thinking in other kinds of play – they’re building or drawing, or we hear them talking. That’s often missing from the digital world, but that doesn’t mean it’s not happening. Asking those questions might make us more aware of what they’re already doing.

Parents are often concerned about their kids’ gaming habits because they can be addicting and keep them on their screens. How can parents manage their kids’ screen time while also trying to have these conversations and develop a better understanding of the intrinsic motivation of video games?

AB: At the end of the day, just like all other things we deal with as parents, we get to decide what’s available and when. I always find it interesting when I hear parents saying their kid is upset when they’re told to turn their device off, or their kid is always asking when they can play again. Would we have the same reaction if they asked us over and over again if their friend was going to come over or when they’re going to soccer? The answer is probably no, and it’s not because the behavior is different; it’s because maybe we don’t see value in the games or we’re concerned about something in the game like it might be a waste of their time.

Kids are allowed to dislike decisions we make as parents. They dislike a lot of decisions we make, and that doesn’t mean we’re going to stop making them. Kids protest bedtime, and they protest leaving the playground, but we don’t stop taking them to playgrounds. We find ways of helping them manage their feelings because we want them to be able to leave the playground one day without having a meltdown.

Screens should be a benefit for our whole family. If you’re allowing screen time for your child, you’re probably getting something out of it too. You’re able to make dinner or answer emails or have a little downtime, and that is perfectly valid. However, if our kid is watching or playing something and we have to navigate a 25-minute meltdown when it gets turned off, maybe that’s not benefitting us anymore.

That doesn’t mean we say, “Never mind, no screens ever again.” We can get curious. We can say, “Okay. What if we tried five minutes less? What if we tried earlier in the day? What if we tried a different show or game and see if there’s any difference?” When we get more inquisitive and experimental, then we can find ways to make it work for everyone in the family.

You’ve suggested gaming with your kids. If a parent has never gamed before, how can they approach starting, and how will it benefit them?

AB: It’s funny because kids start gaming and they don’t have experience either, but then adults try and say, “I wouldn’t possibly know how.” Your seven-year-old figured it out. You probably can, too.

It definitely depends on the game. Some kids won’t want a beginner player weighing them down, but I think a lot of kids are probably pretty delighted by the idea of teaching their adult something. Kids don’t get to be the expert in something, and even if they are, we tend to know more than they do. If we show up to our kids’ interests and say, “I want to do this with you – show me how,” kids are probably going to enjoy that.

You can also think about what you would enjoy doing together. Maybe you would enjoy something collaborative where you’re working together, or maybe something more short-lived and competitive like Mario Kart where you’re racing against each other.

Often, gaming brings up great ways of modeling skills. You can model how to be a gracious loser, how to tolerate frustration, or how to lose and try again. Some people will say, “You can teach that outside of a game,” and of course you can! And you can also teach it within a game, and when you choose that, it’s an immersive environment, and emotions get heightened. In some ways, that makes it a great place to teach those skills. It might give them a framework to use when they encounter the same emotions outside of a game.

What games do you recommend to parents getting started gaming on their own or with their kids?

AB: It depends on your family dynamic. One of the reasons I love the new Mario Kart is because it’s a great way to introduce games to your kid so that you can play together and both be successful. You can toggle on and off different levels of accessibility and automation depending on the kid’s age and skill level. I like games where you can both be in your separate levels of difficulty, but you’re exploring the same space.

A more exploratory game that I think is great for parents to play on their own or two-player is this silly little game called Untitled Goose Game. It’s very simple, there’s no dialogue, and you get to wander around and beat these little objectives. It’s very quaint and sweet.

One that I think is a great party game for families is a game called WarioWare: Get it Together! WarioWare games are micro games where you’re given an objective with five seconds to do it. It’s very fast and very absurd. You have to pay attention, but it’s silly, and if you fail it’s not a big deal, so the stakes are low.

If you’re looking for something calmer, the newest Animal Crossing is a game both adults and kids will like because you can garden, decorate your house, and wander around. For adults revisiting games, The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild and Super Mario Odyssey are both amazing revisits to the franchise. They can reignite that feeling of exploring and adventuring.

Ash Brandin, photo provided

Learn more from Ash Brandin on Instagram, and check out our other blogs about navigating the digital world with kids:

Family Safety Expert Shares Secrets of the Digital World

Why You Need to Abandon Virtual Chat Rooms and Reinvent Your Group Chats

Categories:

About: Kosciusko Connect

You May Be Interested In:

How Does Arlo AI-Powered Motion Detection Work?

3 months ago by Laura Seney

Top 5 Things to Look for in a Security Camera System

6 months ago by Kosciusko Connect

The Future of Connectivity: Why Fiber Internet is Revolutionizing Warsaw, Indiana

8 months ago by Kosciusko Connect

Easter Coloring Contest

1 year ago by Kosciusko Connect

Ready to Get Connected?

Do you have questions or need assistance? Our customer service team is just a call or click away. Contact us today for personalized help!